XIII. Gustave Doré

XIII. Gustave Doré’s Illustrations for Rabelais and Balzac’s Drolatiques

In the time of the Second French Empire of Napoleon III (1852 to 1870), it was none other than the incredibly versatile and inexhaustible Gustave Doré who took up a central position in French book illustration - even though he himself would have rather worked as a "free" artist. Out of his numerous works, we have picked two works for this display, which in the history of their editions already represent a significant time span.

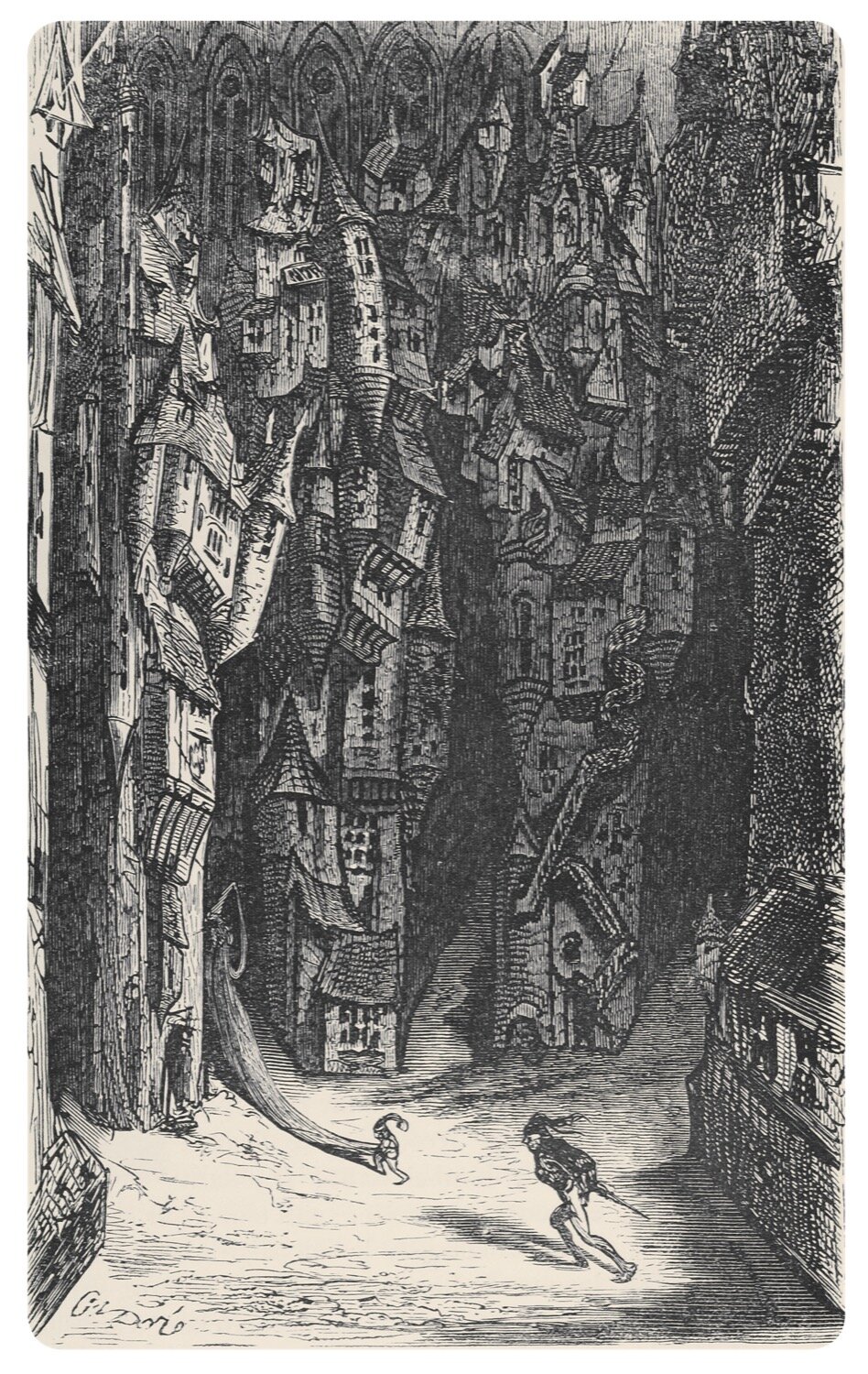

It was the unruly days of the early modern period of the Renaissance that had once brought forth the works of François Rabelais. Many years later, in the very different time of the 19th century, a 22 year old Gustave Doré set about illustrating Rabelais’s novel about the giants Gargantua et Pantagruel, creating around 100 images that oscillate between the whimsical and the uncanny, between realism and fantasy. Two decades after this first 1854 edition, Doré was given the opportunity to approach the subject again and at a larger scale: in 1873, Garnier published a large-size luxury edition with roughly 700 illustrations. The copy presented here [no. 528] is simply untouchable in its significance and rarity: it is the only copy ever printed on strong white calf parchment, a material which in and of itself conjures up the atmosphere of Rabelais’s Renaissance. Once owned by the publisher Garnier himself, the copy was bound by Émile Mercier.

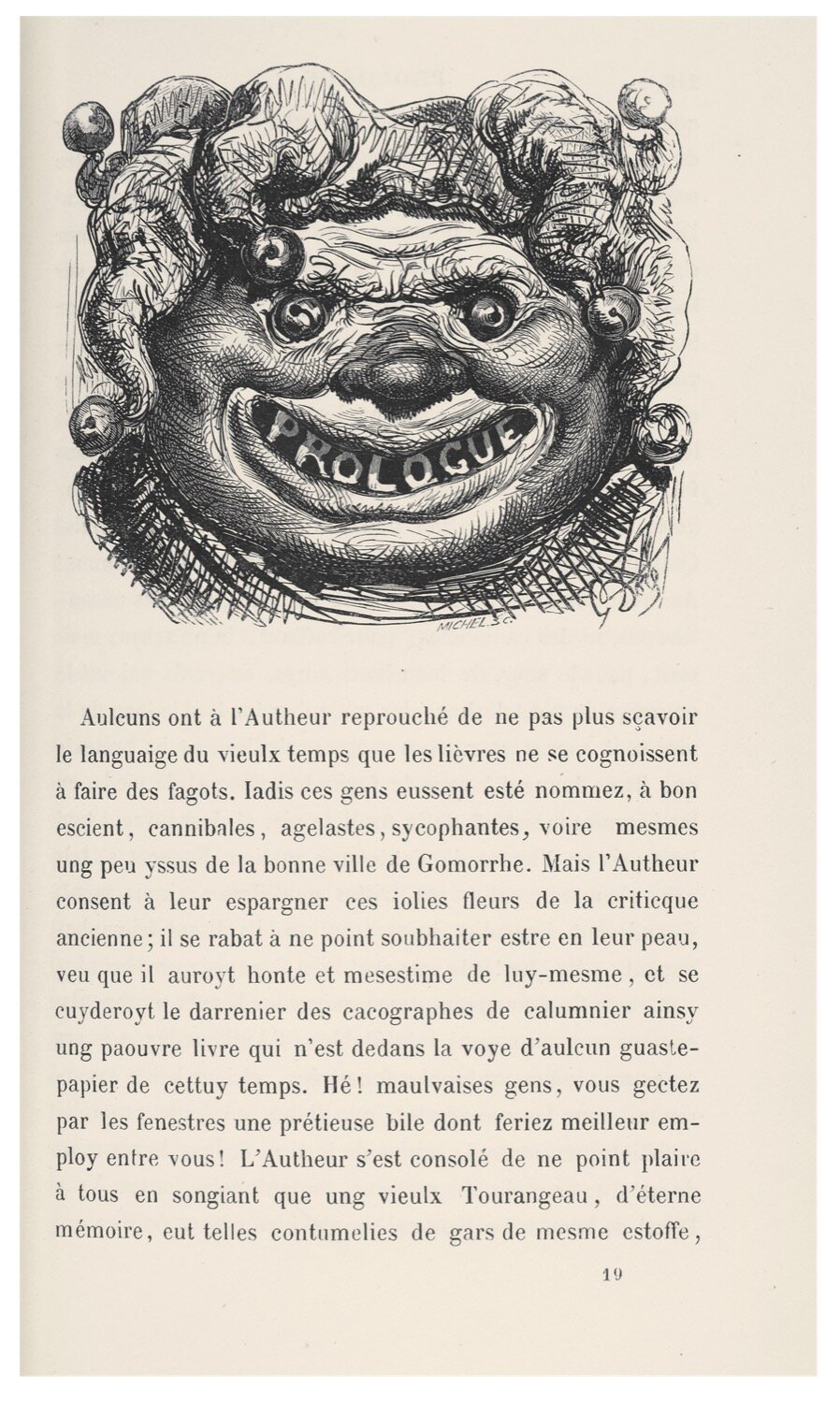

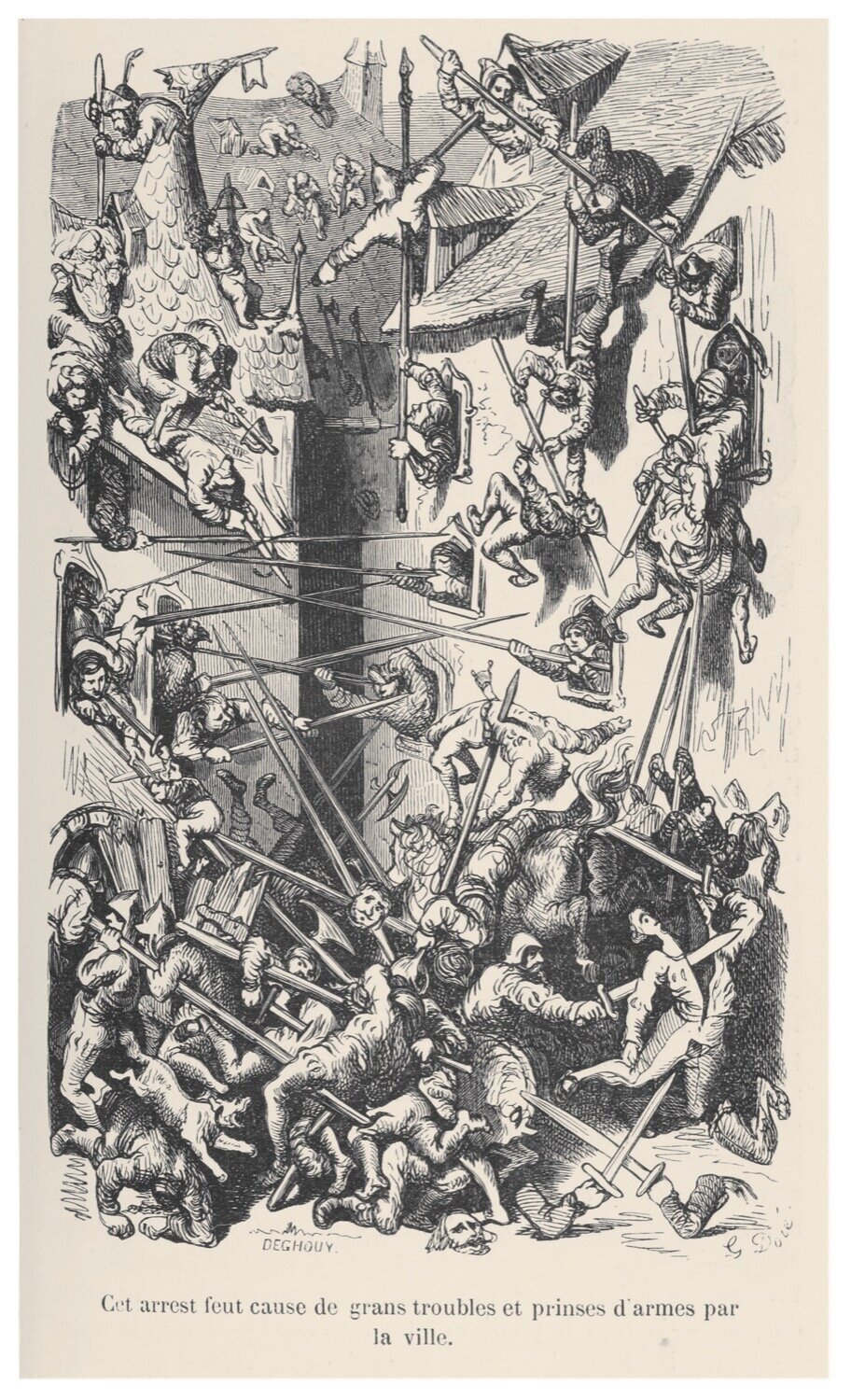

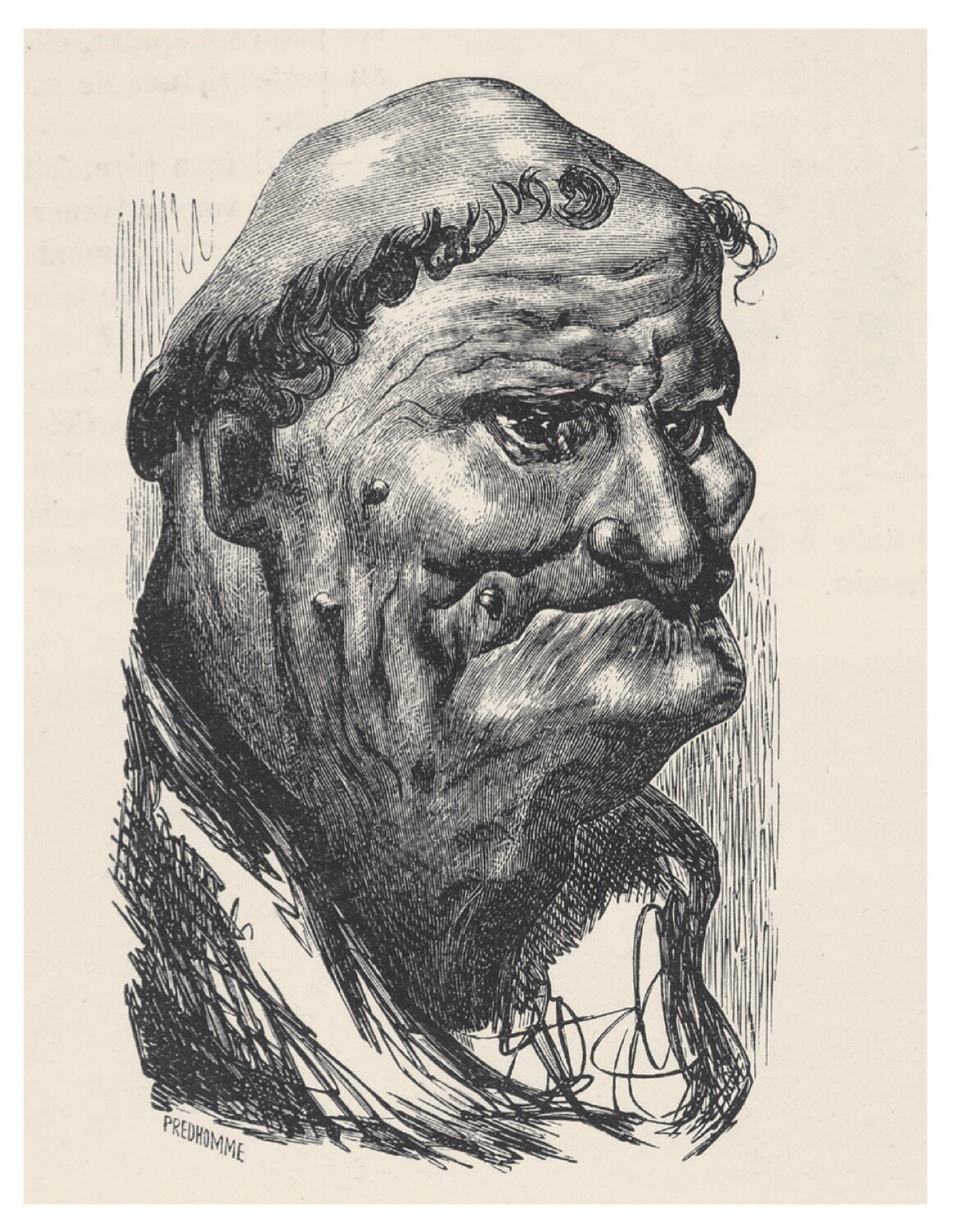

After his work on the Rabelais novel, it only made sense that Doré would in 1855 also illustrate Balzac’s Droll Stories (Les contes drolatiques), since those tales were written in the same archaic voice of the laughing and life-affirming Renaissance man as Rabelais’s text. Maybe these tales particularly resonated with Doré because they reminded him of the mysterious atmosphere of his childhood, which he had spent in the middle of the medieval city of Strasbourg. Léopold Carteret regarded the more than 400 wood engravings produced for this edition as Doré’s masterpiece. This display shows two copies on China paper. The first comes in a green morocco binding by Reymann [no. 26], which used to be in the libraries of the collectors Charles Bouret, Antoine Vautier, and Raphaël Esmerian. The second copy [no. 27] was bound in dark red morocco by Petit and used to belong to Balzac’s wife, Eweline Hanska!

But even later editions of this sought-after work are outstanding bibliophilic prizes: for example the copy of the 1861 edition on China paper in a mosaic binding by Petit, from the collections of Maurice Escoffier, as well as Licin and André Tissot-Dupont [no. 28].

![Doré’s illustrations for the large-scale luxury edition of Gargantua et Pantagruel , from a unique copy printed on white calf parchment [no. 528]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b02a5098ab7225ab8d3a10c/1594144763548-RD2J6HUQM7WGECBLNTGT/528a.jpg)

![Doré’s illustrations for the large-scale luxury edition of Gargantua et Pantagruel , from a unique copy printed on white calf parchment [no. 528]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b02a5098ab7225ab8d3a10c/1594144764113-OA67GEOQPTZ2RGFHNNL9/528b.jpg)

![Doré’s illustrations for the large-scale luxury edition of Gargantua et Pantagruel , from a unique copy printed on white calf parchment [no. 528]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b02a5098ab7225ab8d3a10c/1594145780590-FLPMCWX5I6Y65EVVBQK6/528c.jpg)

![Colourfully-bound copies [nos. 26, 27, 28]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b02a5098ab7225ab8d3a10c/1594144867227-5UYT1W3V8GS6FCNR00HQ/26.jpg)

![Colourfully-bound copies [nos. 26, 27, 28]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b02a5098ab7225ab8d3a10c/1594144910059-ORRXCAHTZBFZNT1VD4NN/27.jpg)

![Colourfully-bound copies [nos. 26, 27, 28]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b02a5098ab7225ab8d3a10c/1594145131718-W0VA3VV4QU5EBJE1ZG0L/28.jpg)